Bonds are issued by many different entities, from the U.S. government to cities and corporations, as well as international bodies. Some bonds, such as mortgage-backed securities, can be issued by financial institutions. Thousands of bonds are issued each year, and even though bonds may share the same issuer, it’s a pretty good bet that each bond is unique.

Learn about the most common types of bonds, and key characteristics of each.

GOVERNMENT BONDS

Government Bonds (“Treasuries”) are issued by the government of a country and are considered to be among the safest investments you can make, because all Treasury securities are backed by the government. There are other features of Treasuries that are appealing to the individual investor.

Treasuries come in three varieties:

-Treasury Bills

Short-term securities that are non-interest bearing (zero-coupon) with maturities of only a few days (these are referred to as cash management bills), four weeks, 13 weeks, 26 weeks or 52 weeks. Also called T-bills, you buy them at a discount to face value (par) and are paid the face value when they mature.

-Treasury Notes

Fixed-principal securities issued with maturities of two, three, five, seven and 10 years. Sometimes called T-Notes, interest is paid semi-annually, with the principal paid when the note matures.

-Treasury Bonds

Long-term, fixed-principal securities issued with a 30-year maturity. Outstanding fixed-principal bonds have terms from 10 to 30 years. Interest is paid on a semi-annual basis with the principal paid when the bond matures.

MORTGAGE-BACKED SECURITIES

Unlike most bonds that pay semi-annual coupons, investors in mortgage-backed securities receive monthly payments of interest and principal. This security is widely traded in the U.S. and other international markets.

Mortgage-backed securities, called MBS, are bonds secured by home and other real estate loans. They are created when a number of these loans, usually with similar characteristics, are pooled together. For instance, a bank offering home mortgages might round up $10 million worth of such mortgages. That pool is then sold to a U.S. federal government agency like Ginnie Mae or a U.S. government sponsored-enterprise (GSE) such as Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, or to a securities firm to be used as the collateral for the new MBS.

The majority of MBSs are issued or guaranteed by an agency of the U.S. government such as Ginnie Mae, or by GSEs, including Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. MBS carry the guarantee of the issuing organization to pay interest and principal payments on their mortgage-backed securities. While Ginnie Mae’s guarantee is backed by the “full faith and credit” of the U.S. government, those issued by GSEs are not.

A third group of MBSs is issued by private firms. These “private label” MBS are issued by subsidiaries of investment banks, financial institutions, and homebuilders whose credit-worthiness and rating may be much lower than that of government agencies and GSEs.

Because of the general complexity of MBS, and the difficulty that can accompany assessing the creditworthiness of an issuer, use caution when investing. They may not be suitable for many individual investors.

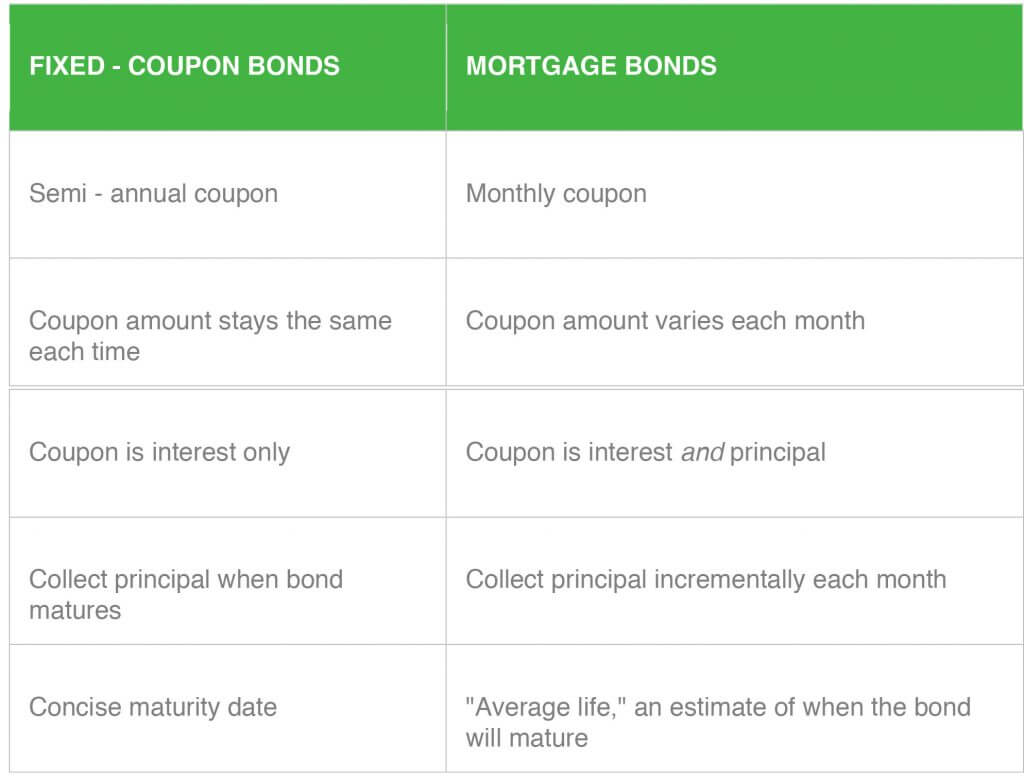

Unlike a traditional fixed-income bond, most MBS bondholders receive monthly—not semi-annual— interest payments. There’s a good reason for this. Homeowners (whose mortgages make up the underlying collateral for the MBS) pay their mortgages monthly, not twice a year. These mortgage payments are what ultimately find their way to MBS investors.

There’s another difference between the proceeds investors get from MBS and, say, a Treasury bond. The Treasury bond pays you interest only—and at the end of the bond’s maturity, you get a lump-sum principal amount, say $1,000. But a MBS pays you interest and principal. Your cash flow from the MBS at the beginning is mostly from interest, but gradually more and more of your proceeds come from principal. Since you are receiving payments of both interest and principal, you don’t get handed a lump-sum principal payment when your MBS matures. You’ve been getting it in portions every month.

MBS payments (cash flow) may not be the same each month because the original “pass-through” structure reflects the fact that homeowners themselves don’t pay the same amount each month.

There’s one more thing about those portions you’ve been getting—they are not the same each month. For this reason, investors who draw comfort from a dependable and consistent semi-annual payment may find the unpredictability of MBS unsettling.

Here are some of the most common types of mortgage-backed securities:

Pass – Throughs: The most basic mortgage securities are known as pass-throughs. They are a mechanism—in the form of a trust—through which mortgage payments are collected and distributed (or passed through) to investors. The majority of pass-throughs have stated maturities of 30 years, 15 years and five years. While most are backed by fixed-rate mortgage loans, adjustable-rate mortgage loans (ARMs) and other loan mixtures are also pooled to create the securities. Because these securities “pass through” the principal payments received, the average life is much less than the stated maturity life, and varies depending upon the pay-down experience of the pool of mortgages underlying the bond.

Collateralized mortgage obligations: Called CMOs for short, these are a complex type of pass-through security. Instead of passing along interest and principal cash flow to an investor from a generally like-featured pool of assets (for example, 30-year fixed mortgages at 5.5 percent, which happens in traditional pass-through securities), CMOs are made up of many pools of securities. In the CMO world, these pools are referred to as tranches, or slices. There could be scores of tranches, and each one operates according to its own set of rules by which interest and principal gets distributed. If you are going to invest in CMOs—an arena generally reserved for sophisticated investors—be prepared to do a lot of homework and spend considerable time researching the type of CMO you are considering (there are dozens of different types), and the rules governing its income stream.

Many bond funds invest in CMOs on behalf of individual investors. To find out whether any of your funds invests in CMOs, and if so, how much, check your fund’s prospectus.To recap, both pass-throughs and CMOs differ in a number of significant ways from traditional fixed-income bonds.

FIXED-COUPON BONDS AND MORTGAGE BONDS

There are a number of ways that mortgage-backed securities, such as pass-throughs and CMOs, differ from more traditional fixed-income bonds, such as corporate and municipal bonds. The chart below provides a comparison of a number key bond factors.

CORPORATE BONDS

Companies issue corporate bonds (or corporates) to raise money for capital expenditures, operations and acquisitions. Corporates are issued by all types of businesses, and are segmented into major industry groups.

Corporate bondholders receive the equivalent of an IOU from the issuer of the bond. But unlike equity stockholders, the bondholder doesn’t receive any ownership rights in the corporation. However, in the event that the corporation falls into bankruptcy and is liquidated, bondholders are more likely than common stockholders to receive some of their investment back.

There are many types of corporate bonds, and investors have a wide-range of choices with respect to bond structures, coupon rates, maturity dates and credit quality, among other characteristics. Most corporate bonds are issued with maturities ranging from one to 30 years (short-term debt that matures in 270 days or less is called “commercial paper”).

Bondholders generally receive regular, predetermined interest payments (the “coupon”), set when the bond is issued. Interest payments are subject to federal and state income taxes, and capital gains and losses on the sale of corporate bonds are taxed at the same short- and long-term rates (for bonds held for less, or for more, than one year) that apply when an investor sells stock.

Corporate bonds tend to be categorized as either investment grade or non-investment grade. Non-investment grade bonds are also referred to as “high yield” bonds because they tend to pay higher yields than Treasuries and investment-grade corporate bonds. However, with this higher yield comes a higher level of risk. High yield bonds also go by another name: junk bonds. Most corporate bonds trade in the over-the-counter (OTC) market. The OTC market for corporates is decentralized, with bond dealers and brokers trading with each other around the country over the phone or electronically.

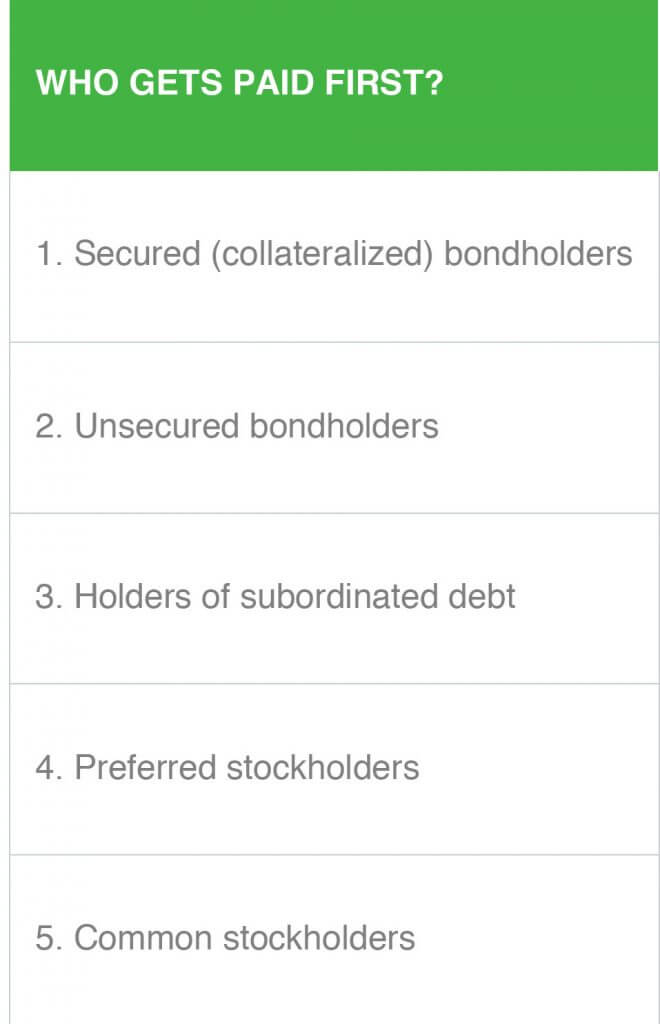

There are two concepts that are important to understand with respect to corporate bonds. The first is that there are classifications of bonds based on a bond’s relationship to a corporation’s capital structure. This is important because where a bond structure ranks in terms of its claim on a company’s assets determines which investors get paid first in the event a company has trouble meeting its financial obligations. Secured Corporates: In this ranking structure, so-called senior secured debt is at the top of the list (senior refers to its place on the pay-out totem pole, not the age of the debt).

Secured corporate bonds are backed by collateral that the issuer may sell to repay you if the bond defaults before, or at, maturity. For example, a bond might be backed by a specific factory or piece of industrial equipment. Junior or Subordinated Bonds: Next on the pay-out hierarchy is unsecured debt—debt not secured by collateral, such as unsecured bonds. Unsecured bonds, called debentures, are backed only by the promise and good credit of the bond’s issuer. Within unsecured debt is a category called subordinated debt—this is debt that gets paid only after higher-ranking debt gets paid.

The more junior bonds issued by a company typically are referred to as subordinated debt, because a junior bondholder’s claim for repayment of the principal of such bonds is subordinated to the claims of bondholders holding the issuer’s more senior debt.